Edvard Munch

As a rare Munch show opens in Britain, we travel to Norway to find the forces that unleashed his macabre art – from flame-haired Medusas to primal screams

Edvard Munch: booze, bullets and breakdowns

Claire Armitstead in Oslo

@carmitstead

Mon 8 Apr 2019 16.07 BSTLast modified on Mon 8 Apr 2019 18.50 BST

Shares

911

Comments66

Vampire II, 1896, by Edvard Munch. Photograph: Henie Onstad Kunstsenter

Hidden away in the basement of Oslo’s Munch Museum lies a treasure trove. Here you’ll find madonnas and vampires, lions and tigers alongside the hefty white blocks from which they were printed, still blackened with printers’ ink. It feels like being conducted around the inside of Edvard Munch’s brain.

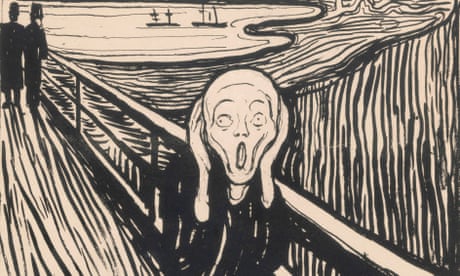

You might also spot, resting on an easel, a stunning early colour version of The Scream, scribbled with a rough urgency in pastel on cardboard, and therefore too fragile to be subjected to daylight. The distressed little figure, blocking its ears in horror against the scream of nature, has been described as the ultimate image for our catastrophic times. By far the best known Munch work outside his homeland, it is one of the few fine-art images to have its own emoji.

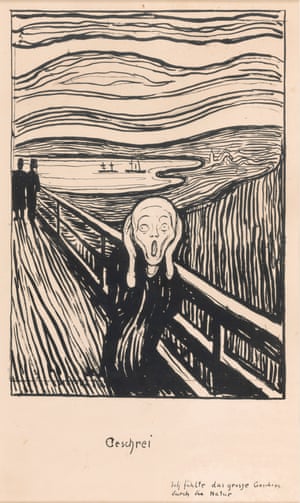

A lithograph version of The Scream, 1895, by Edvard Munch. Photograph: Thomas Widerberg

A lithograph version of The Scream, 1895, by Edvard Munch. Photograph: Thomas WiderbergThe Munch Museum is not too lofty to cash in on Scream merchandise, selling baby grows and tea towels, with more exotic novelty items displayed in a cabinet of curiosities from abroad (as a belatedly reformed alcoholic, Munch might have appreciated the Scream vodka bottles.) But it is also on a mission to challenge that painting’s monolithic reputation. Which is why it has partnered with British Museum in London on Edvard Munch: Love and Angst, an exhibition that promises to throw fresh light on an artist whose work is rarely shown in the UK.

The show will include a black-and-white lithograph of The Scream, on loan from a private Norwegian collector. But it presents the picture alongside more than 80 other works, making the case for Munch as one of art history’s most innovative and expressive printmakers, an artist who said, “I don’t paint what I see but what I saw,” obsessively reframing his memories using the printmaking technologies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

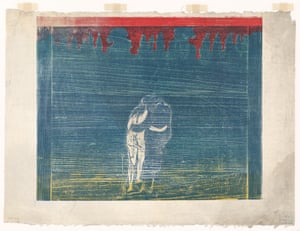

FacebookTwitterPinterest Towards the Forest I, 1897, by Edvard Munch. Photograph: Halvor Bjørngård

Advertisement

One of the most revelatory works I spot in the Munch Museum’s basement is a series of woodcuts that lines its walls. Towards the Forest – three impressions of which will appear at the British Museum – features a man and a woman walking arm-in-arm towards a wood. The palette varies widely, with the sky, the grass and the couple picked out in different colours to create very different moods. Some are ominous, some wistful and others hazily romantic. In some, the woman is wearing a long dress; in others her legs are bare.

Sign up to the Art Weekly email

Read more

It seems a mystery how a single image could be so various until we are ushered towards a nearby bench to view the pair of woodblocks from which the prints were made. Delicately jigsawed into three pieces, with chunks missing, they are “the most complicated ever produced”, according to Giulia Bartrum, who curates the British Museum show. “Traditionally, woodblocks are in one colour and printed sequentially. But Munch found that if he chopped the blocks up he could ink the pieces separately, then fit the block together and print in one movement. Every impression is different, and there are 50 to 60 still in existence.”

To see the versions of a Munch print side by side is to understand something of the compulsion that drove him to repeat the same images again and again. One of the earliest and most familiar is The Sick Child, a haunted deathbed scene in which – over more than 40 years from his early 20s – he revisited the final hours of his older sister, Sophie, as she succumbed to the tuberculosis that he was convinced would eventually kill him, too.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Edvard Munch’s 1896 painting The Sick Child. Photograph: AP

Advertisement

It was the picture that made his reputation in mainland Europe, causing such a furore in Germany in 1892 over its technique (one critic called it “a discarded, half-rubbed out sketch”) that the Berlin Artist Association, under pressure from the kaiser, voted to close the show. By then Munch was deep into the alcoholic spiral that would generate his most powerful work and lead to a breakdown in his mid-40s. His bohemian set included writers and theatre-makers; a section of the London exhibition is dedicated to his work for the stage, including a 1906 set design for Ghosts, Ibsen’s portrait of Norway’s syphilitic society.

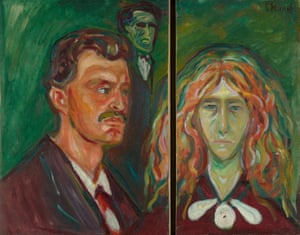

While he was working on The Sick Child, Munch also painted an early version of his erotic Madonna, which he gave to an imprisoned anarchist friend to decorate his jail cell. (A later version emphasised her orgasmic state by encircling the image with sperm and foetuses.) But his celebrations of love were offset by his terror of romantic entanglement – often embodied, as Bartrum points out, in women with Medusa-like red hair. One painting, Self-Portrait With Tulla Larsen, memorialises a particularly turbulent relationship, which ended with a bang in 1902, when he was accidentally shot. (Among the Munch Museum’s more macabre possessions is an x-ray of his left hand showing the bullet lodged in his ring finger.) In his distress, Munch cut the painting in two; it will appear at the British Museum in its bifurcated state.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Madonna, 1895/1902, by Edvard Munch. Photograph: Ove Kvavik/Munchmuseet

There is bound to be plenty of interest in the show. Norway doesn’t often make the international news, but of the 20,000 to 30,000 headlines it does generate around the world each year, a quarter are about Munch. This startling statistic is rattled off by Stein Olav Henrichsen, director of the Munch Museum and the person responsible for moving it to a new home on the city’s waterfront, due to open in June 2020. Staff are already hard at work packing up the 45,000 objects bequeathed to Oslo by the artist on his death in 1944, including 1,100 paintings, 6,800 drawings and 18,200 works of graphic art – not to mention the 10,000 letters and other pieces of text.

The new 13-storey picture palace – which will be one of the largest monographic museums in the world – will include two floors for temporary exhibitions of other artists whose work is in dialogue with Munch’s. Among the most prominent of these is Tracey Emin, who will not only be the first guest to feature when the museum opens, but will have a permanent presence as part of a buzzy new waterfront cultural quarter when her seven-metre bronze sculpture, The Mother, is unveiled on its own island at the mouth of Munch’s beloved Akerselva River.

Advertisement

It is ironic that a British artist should be chosen for this honour, since UK collectors were slow to appreciate Munch, only catching on after his death. How was this talented reprobate viewed among his compatriots at the time? One answer lies in Oslo’s Frogner Park, where the monumental sculptures of his contemporary and rival Gustav Vigeland – a local hero virtually unknown outside his home country – command the landscape. Much to Munch’s chagrin, Vigeland was given a grand studio and park by the city of Oslo. Both are now landmarks.

FacebookTwitterPinterest The two pieces of Self-Portrait With Tulla Larsen, circa 1905, by Edvard Munch. Photograph: Ove Kvavik/Munchmuseet

Advertisement

Munch’s house and studio were on a remote hillside above Oslo, where he fled after his 1908 breakdown to escape “the enemy” – critics and fellow artists. He would live there with his beloved dogs, and the occasional horse, until his death. Liberated from his angst and alcoholism, he painted and repainted the nature around him, jealously hoarding his work while treating it with mind-boggling contempt. He would leave paintings outside in in all weathers beneath a narrow mansard, saying: “It does them good to fend for themselves.”

The house in Ekely has long been demolished but the studio survives, in the shelter of a huge beech tree, which can be seen as a sapling in a series of touching photographs taken during Munch’s lifetime. The studio is hard to reach and opens only sporadically to the public, but offers residencies to artists, the most recent of whom, Olav Ringdal, is in the final stages of preparing an exhibition. Ringdal admits to finding Munch’s legacy “a bit irritating … I wish I was a Dutch artist, because they have the whole spectrum. Here there is only Munch.” In an elegantly minimalist downtown gallery, the artist AK Dolven takes a different view. The centrepiece of her small show is a bed carved from pink, candy-striped Arctic marble, which visitors can touch and even lie on, and which she describes as “a conversation with Munch”.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Edvard Munch with brush and palette with his canvases at his house outside Oslo. Photograph: Munchmuseet

In Oslo’s elaborately painted city hall – the setting for the annual Nobel peace prize ceremony – there is no public sign of Munch, because he declined to enter a competition to decorate its civic centre. But his presence is everywhere in corridors and committee rooms; there is even a mythologically charged cycle of 19 lithographs, Alpha and Omega, which he designed while recovering from his breakdown.

Edvard Munch: Scandi novelists on the master of misery and menace

Read more

Charting the relationship of a couple marooned on an island, it ends with a tiger possessing the woman and killing the man. Munch drew animals beautifully, visiting zoos to study them. But he wrote: “We want more than a mere photograph of nature. We do not want to paint pretty pictures to be hung on drawing room walls. We want to create, or at least lay the foundations of, an art that gives something to humanity. An art that arrests and engages. An art created of one’s innermost heart.”

His ambition is echoed in a scrawl by Emin on an early sketch of the statue that will command Oslo harbour for future generations: “The Mother sits on Museum Island [with] her legs open – towards the fjord. She is welcoming all of nature. She is the companion of the ghost of Munch.”

• Munch: Love and Angst is at the British Museum, London, from 11 April until 21 July.

Topics

Edvard Munch

Illustration

Painting

Norway

Art

Design

Europe

features

Link:

No comments:

Post a Comment