Adapt, cope, remain flexible and foster a positive attitude amidst life's ups and downs

Change

Adapt, cope, remain flexible and foster a positive attitude amidst life's ups and downs.

Wednesday, November 28, 2018

Monday, November 26, 2018

Share your inspiration with others

Keep your fears to Yourself, butShare your inspiration with others

-- Robert Louis Stevenson

Sinclair Lewis/Quotes

When facism comes to America it will be wrapped in the flag and carrying a cross.

Winter is not a season, it's an occupation.

It is impossible to discourage the real writers - they don't give a damn what you say, they're going to write.

What is love? It is the morning and the evening star.

Advertising

is a valuable economic factor because it is the cheapest way of selling

goods, particularly if the goods are worthless.

Intellectually

I know that America is no better than any other country; emotionally I

know she is better than every other country.

People will buy anything that is one to a customer.

There are two insults no human being will endure: that he has no sense of humor, and that he has never known trouble.

Our American professors like their literature clear and cold and pure and very dead.

Pugnacity is a form of courage, but a very bad form.

Friday, November 16, 2018

‘No Morals’: Advertisers React to Facebook Report

One senior adviser in advertising suggested that Facebook should establish an ombudsman role to assess and report on its societal risks in regular financial filings.CreditCreditPhilippe Wojazer/Reuters

‘No Morals’: Advertisers React to Facebook Report

By Sapna Maheshwari

Nov. 15, 2018

Advertisers are the financial engine of Facebook, but lately the relationship had gotten rocky.

It got rockier on Thursday.

Several top marketers were openly critical of the tech giant, a day after The New York Times published an investigation detailing how Facebook’s top executives — Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg — made the company’s growth a priority while ignoring and hiding warning signs over how its data and power were being exploited to disrupt elections and spread toxic content. The article also spotlighted a lobbying campaign overseen by Ms. Sandberg, who also oversees advertising, that sought to shift public anger to Facebook’s critics and rival tech firms.

The revelations may be “the straw that breaks the camel’s back,” said Rishad Tobaccowala, chief growth officer for the Publicis Groupe, one of the world’s biggest ad companies. “Now we know Facebook will do whatever it takes to make money. They have absolutely no morals.”

Marketers have grumbled about Facebook in the past, concerned that advertisements could appear next to misinfor

mation and hate speech on the platform. They have complained about how the company handles consumer data and how it measures ads and its user base. But those issues were not enough to outweigh the lure of Facebook’s vast audience and the company’s insistence that it was trying to address its flaws.

And after this article was published online, Mr. Tobaccowala called The New York Times to add to his comments.

“The people there do,” he said, referring to possessing morals, “but as a business, they seem to have lost their compass.”

And while ad agencies or their holding companies, like Publicis, place money on behalf of brands, it is up to the brands to decide whether to advertise on Facebook.

“Agencies can make recommendations, but marketers need to decide at what point is this going to be a liability for them,” said Marla Kaplowitz, chief executive of the 4A’s, an industry trade group.

So far, very few have been willing to leave the platform.

“Advertisers have long taken the position that Facebook was gamed by third parties and bad actors but had always believed that Facebook was taking whatever steps it could to prevent that,” said Rob Norman, a senior adviser at GroupM, the media buying arm of the ad giant WPP, and a longtime industry watcher.

Mr. Norman said Facebook should establish an ombudsman role to assess its societal risks, with reports in its regular financial filings. He compared the work to an accounting firm’s audit of a corporation’s finances.

“The business should be obliged to report its risk to society versus just financial risks to the business,” Mr. Norman said.

“We’ve made mistakes, but to suggest that we aren’t focused on uncovering and tackling issues quickly is not true,” Carolyn Everson, the vice president of global marketing solutions at Facebook, said in an emailed statement. “Our clients depend on us to help drive their business, and whether that means supporting the largest brands in the world or budding entrepreneurs, we’ll stay focused on doing the best work for our partners, improving safety and security across our platforms, and driving social good in the world.”

Almost all of Facebook’s revenue — which climbed to just over $40 billion last year — comes from advertisers, which range from local businesses to global brands. Along with Google, Facebook dominates the digital advertising market, and even as user growth has slowed, its revenue has risen quarter after quarter. But marketing is built on trust between sellers and buyers, and the revelations this week are a jolt for some in the industry.

“Up to now, whatever you said about Facebook, you couldn’t say it was a two-faced company,” Mr. Tobaccowala said. “It says one thing to you and does something completely different. This is very hard if you are a marketer.”

He added: “I’m not anti-Facebook. But I have always believed that marketers need people who recognize their dollars, and that they should drive and control their brands and they should control their data, and I think this will probably give them additional gumption to stand up and be heard.”

R/GA, a digital agency that won an advertising award from Facebook last year, posted a link to the Times article on Twitter and added, “It’s time to admit we were all wrong about Facebook. It’s actually worse.” The agency declined to comment further.

Dave Morgan, the founder and chief executive of Simulmedia, which works with advertisers on targeted television ads, said the reports about Facebook’s behavior “are driving a lot of pretty intense conversations in the ad industry these days.”

“What I hear most are brands saying that time for just talking is over: ‘It’s no longer about what Facebook says, it’s about what they do and what they stop doing,’” he said.

Keith Weed, the chief marketing officer for Unilever, created a stir this year when he said the company would not invest in platforms or environments “which create division in society, and promote anger or hate.” Unilever, one of the world’s biggest advertisers and the owner of brands like Dove and Lipton, said it would “prioritize investing only in responsible platforms that are committed to creating a positive impact in society.”

Unilever did not respond to a request for comment on Thursday.

“So far, the track record basically has been that regardless of what Facebook does, they keep getting more money,” Mr. Tobaccowala said. “The question simply is, will this make people wake up?”

Email Sapna Maheshwari at sapna@nytimes.com or follow her on Twitter: @sapna.

A version of this article appears in print on Nov. 15, 2018, on Page B4 of the New York edition with the headline: ‘No Morals’: Advertisers Voice Criticism of Tech Giant.

Related Coverage

Delay, Deny and Deflect: How Facebook’s Leaders Fought Through CrisisNov. 14, 2018

Damage Control at Facebook: 6 Takeaways From The Times’s Investigation Nov. 14, 2018

Link: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/15/business/media/facebook-advertisers.html

Wednesday, November 14, 2018

Change is a constant

To

begin a new you must say farewell to who you once were. To open a new

door you must close an old one first. That can be heartbreaking and

scary, but it is necessary if you are to change and grow. Say goodbye to

the old you and rise up as a stronger and more magical you.

Sunday, November 11, 2018

The Problem With Being Perfect

The Problem With Being Perfect

A trait that’s often seen as good can actually be destructive. Here’s how to combat it.

Olga Khazan

She’s heard of grad students spending 12 to 18 hours at a time in the lab. Their schedules are meant to be literally punishing: If they’re scientists-in-training, they won’t allow themselves to watch Netflix until their experiments start generating results. “Relationships become estranged—people stop inviting them to things, which leads them to spend even more time in the lab,” Pryor told me.

Along with other therapists, Pryor, who is now with the Family Institute at Northwestern University, is trying to sound the alarm about a tendency among young adults and college students to strive for perfection in their work—sometimes at any cost. Though it is often portrayed as a positive trait—a clever response to the “greatest weaknesses” question during job interviews, for instance—Pryor and others say extreme perfectionism can lead to depression, anxiety, and even suicidal ideation.

What’s more, perfectionism seems to be on the rise. In a study of thousands of American, Canadian, and British college students published earlier this year,

What’s more, perfectionism seems to be on the rise. In a study of thousands of American, Canadian, and British college students published earlier this year, Thomas Curran of the University of Bath and Andrew Hill of York St. John University found that today’s college students report higher levels of perfectionism than college students did during the 1990s or early 2000s. They measured three types of perfectionism: self-oriented, or a desire to be perfect; socially prescribed, or a desire to live up to others’ expectations; and other-oriented, or holding others to unrealistic standards. From 1989 to 2016, they found, self-oriented perfectionism scores increased by 10 percent, socially prescribed scores rose by 33 percent, and other-oriented perfectionism increased by 16 percent.

Curran describes socially prescribed perfectionism as “My self-esteem is contingent on what other people think.” His study didn’t examine the causal reasons for its rise, but he posits that the rise of both standardized testing and social media might play a role. These days, LinkedIn alerts us when our rival gets a new job, and Instagram can let us know how well “liked” our lives are compared with a friend’s.

Michael Brustein, a clinical psychologist in Manhattan, says when he first began practicing in 2007, he was surprised by how prevalent perfectionism was among his clients, despite how little his graduate training had focused on the phenomenon. He sees perfectionism in, among others, clients who are entrepreneurs, artists, and tech employees. “You’re in New York because you’re ambitious, you have this need to strive,” he says. “But then your whole identity gets wrapped into a goal.”

Perfectionism can, of course, be a positive force. Think of professional athletes, who train aggressively for ever-higher levels of competition. In well-adjusted perfectionism, someone who doesn’t get the gold is able to forget the setback and move on. In maladaptive perfectionism, meanwhile, people make an archive of all their failures. They revisit these archives constantly, thinking, as Pryor puts it, “I need to make myself feel terrible so I don’t do this again.”

Then they double down, “raising the expectation bar even higher, which increases the likelihood of defeat, which makes you self-critical, so you raise the bar higher, work even harder,” she says.

Next comes failure, shame, and pushing yourself even harder toward even higher and more impossible goals. Meeting them becomes an “all or nothing” premise. Pryor offered this example: “Even if I’m an incredible attorney, if I don’t make partner in the same pacing as one of my colleagues, clearly that means I’m a failure.”

Brustein says his perfectionist clients tend to devalue their accomplishments, so that every time a goal is achieved, the high lasts only a short time, like “a gas tank with a hole in it.” If the boss says you did a great job, it’s because he doesn’t know anything. If the audience likes your work, that’s because it’s too stupid to know what good art actually is.

While educators and parents have successfully convinced students of the need to be high performing and diligent, the experts told me, they haven’t adequately prepared them for the inevitability of failure. Instead of praises like “You’re so smart,” parents and educators should say things like “You really stuck with it,” Pryor says, to emphasize the value of tenacity over intrinsic talent.

Pryor notes that many of her clients are wary she’ll “turn them into some degenerate couch potato and teach them to be okay with it.” Instead, she tries to help them think through the parts of their perfectionism they’d like to keep, and to lose the parts that are ruining their lives.

Bach, who sees many students from Brown University, says some of them don’t even go out on weekends, let alone weekdays. She tells them, “Aim high, but get comfortable with good enough.” When they don’t get some internship or award, she encourages them to remember that “one outcome is not a basis for a broad conclusion about the person’s intelligence, qualifications, or potential for the future.”

The treatment for perfectionism might be as simple as having patients keep logs of things they can be proud of, or having them behave imperfectly in small ways, just to see how it feels. “We might have them hang the towels crooked or wear some clothing inside out,” says Martin Antony, a professor in the department of psychology at Ryerson University in Toronto.

Brustein likes to get his perfectionist clients to create values that are important to them, then try to shift their focus to living according to those values rather than achieving specific goals. It’s a play on the “You really stuck with it” message for kids. In other words, it isn’t about doing a headstand in yoga class; it’s about going to yoga class in the first place, because you like to be the kind of person who takes care of herself.

But he warns that some people go into therapy expecting too much—an instant transformation of themselves from a pathological perfectionist to a (still high-achieving) non-perfectionist.

They try to be perfect, in other words, at no longer being perfect.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

Related Video

Most Popular

1 The Fading Battlefields of World War I

This year will mark the passing of a full century since the end of World War I. Much of the battle-ravaged landscape along the Western Front has been reclaimed by nature, erasing the scars of the war.Alan Taylor2 A Narcotics Officer Ends His War on Drugs

Kevin Simmers locked up hundreds of drug users—including his own daughter—while the opioid epidemic raged. Now he wants 24-hour treatment on demand.Jeremy Raff3 It’s Probably Too Late to Stop Mueller

The prospects for interference are dimmer than many imagine.Benjamin Wittes4 America Is Divided by Education

The gulf between the party identification of white voters with college degrees and those without is growing rapidly. Trump is widening it.Adam Harris5 Why Trump Is the Favorite in 2020

The Republican Party just suffered big losses in the House of Representatives, but the president is getting ready to ramp up his campaign—and he’s got a good shot at reelection.David A. Graham6 Nancy Pelosi: Mueller Doesn’t Have to Indict Trump for Congress to Impeach Him

But the congresswoman says she isn’t planning to go down that road—yet.Edward-Isaac Dovere

The No. 1 Lifelong Habit Of Warren Buffett: The 5-Hour Rule

Learning

How To Learn Speaker and Teacher / Serial Entrepreneur / Bestselling

Author / Forbes, Fortune, Time, HBR Contributor / Site:

http://t.co/T32xDLUBLJ

I remember the first time I heard that Warren Buffett spends 80 percent of his time reading and thinking, and has done so for his entire career.

I was even more surprised by how Buffett’s long-term business partner describes his weekly schedule:

You look at his schedule sometimes and there’s a haircut.

Tuesday, haircut day.

That’s what created one of the world’s most successful business records in history. He has a lot of time to think.

“WTF?!” I thought myself. “That makes no sense.”

“How can the CEO of a company with hundreds of thousands of employees have so much free time while my schedule is packed?”

“What is the smartest investor in history seeing that I’m not?” I wondered.

After

years of watching nearly every Buffett interview, reading his annual

Letters to Shareholders, reading multiple biographies, and applying the

lessons to my life, I think I finally have the answer to why and how

Buffett has adopted this schedule.

This article shares that answer.

By the end of it, you’ll have a clear path to adopting the 5-Hour Rule

(deliberately learning for at least five hours per week) and moving

much closer to Buffett’s more intensive Learner’s Lifestyle (making

deliberate learning your No. 1 competitive advantage and getting

essentially paid to learn).

But, first, let’s uncover what Buffett sees about knowledge work that most of us don’t.

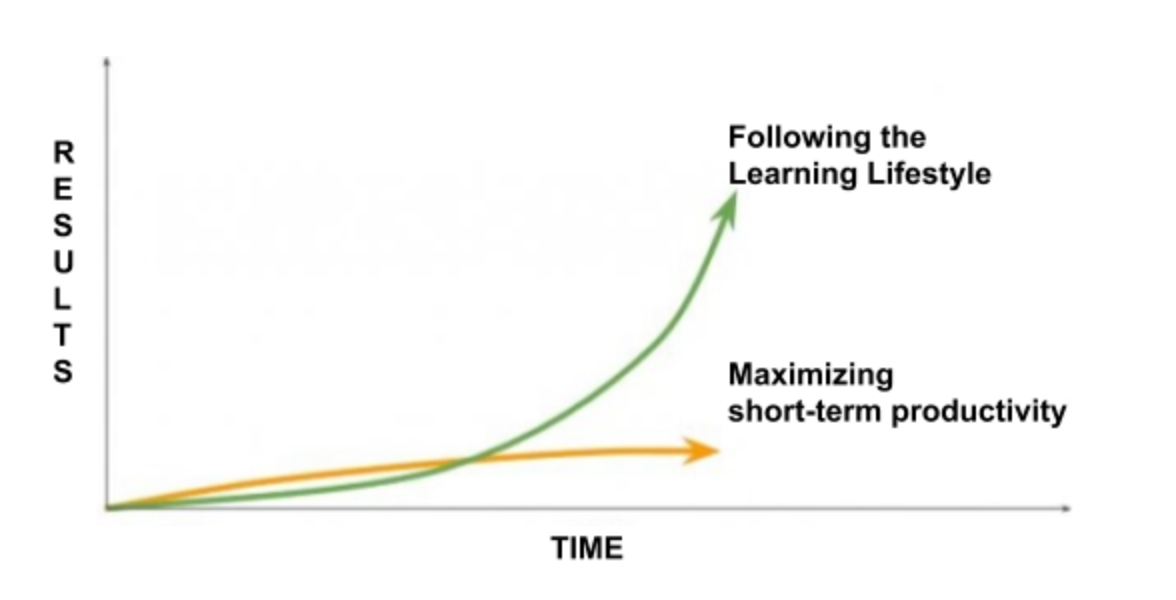

The Case For The Learner’s Lifestyle

In short, all that Buffett research made me realize two things…

First, in a knowledge economy, learning and thinking are the single best long-term investments you can make in your career. Learning and thinking determine our decisions. Then, decisions determine our results.

Second, Buffett’s schedule is a harbinger of a new class of knowledge workers (especially investors, entrepreneurs, designers, developers, coaches, consultants, thought leaders, etc.) who realize that learning and thinking, not just doing, are the keys to their long-term success.

Let’s go a level deeper.

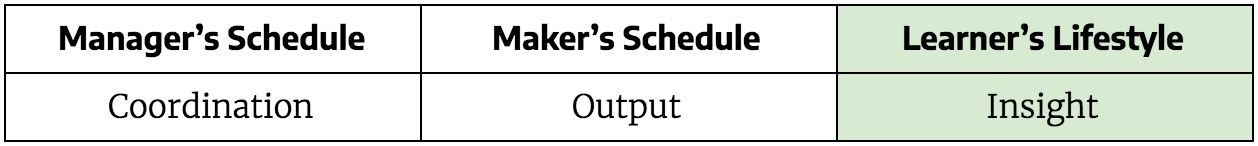

In 2009, Paul Graham, wrote an iconic article called Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule.

Graham is the founder of YCombinator, the most successful startup accelerator in history — backer of AirBnb, Dropbox, Stripe, and Reddit.

In the article, he spells out the difference between two types of schedules in a knowledge economy:

Manager Schedule: The manager’s schedule is for bosses. It’s embodied in the traditional appointment book, with each day cut into one-hour intervals. You can block off several hours for a single task if you need to, but by default you change what you’re doing every hour.

Maker’s Schedule: But there’s another way of using time that’s common among people who make things, like programmers and writers. They generally prefer to use time in units of half a day at least. You can’t write or program well in units of an hour. That’s barely enough time to get started.

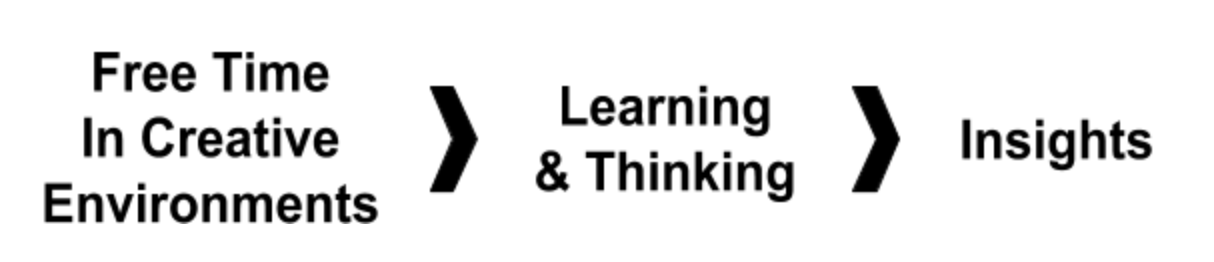

Buffett’s contribution is a third category — the Learner’s Lifestyle.

In short, The Learner’s Lifestyle optimizes for insight over coordination and output. Whereas

the manager’s schedule is primarily about coordination and the maker’s

schedule is about output, the Learner’s Lifestyle is primarily about

insight.

This distinction is simple yet profound.

When we design our life for insight, we organize our schedule completely differently:

- We optimize for free time over busy-ness. Whereas managers must ALWAYS be tuned in and turned on so they can be responsive, thinkers create big blocks of free time to go above the noise and gain perspective.

- We work in environments that lead to more creativity. As I wrote in Why Successful People Spend 10 Hours A Week On “Compound Time”, many of the greatest insights in history have come during a nap or on a walk, not necessarily within a cubicle.

- We invest dramatically more in learning, experimenting, and thinking, because they are the fundamental building blocks of insight. Learning is about acquiring diverse, rare, and valuable chunks of knowledge through People, Information, & Experiences (what I call P.I.E.). Thinking is about synthesizing those chunks into rare and valuable combinations. Experimenting is about seeing how those combinations actually perform in the real world.

- We measure our success by the quality of insights we have, not by how quickly we finish our to do list. In other words, our measure of success moves away from efficiency toward effectiveness.

The #1 Differentiator of the Learner’s Lifestyle

To

put the Learner’s Lifestyle in context, let’s take a step back and

think about what it means to be a knowledge worker in the 21st century.

No one has done a better job of this than Peter Drucker, perhaps the greatest management thinker ever.

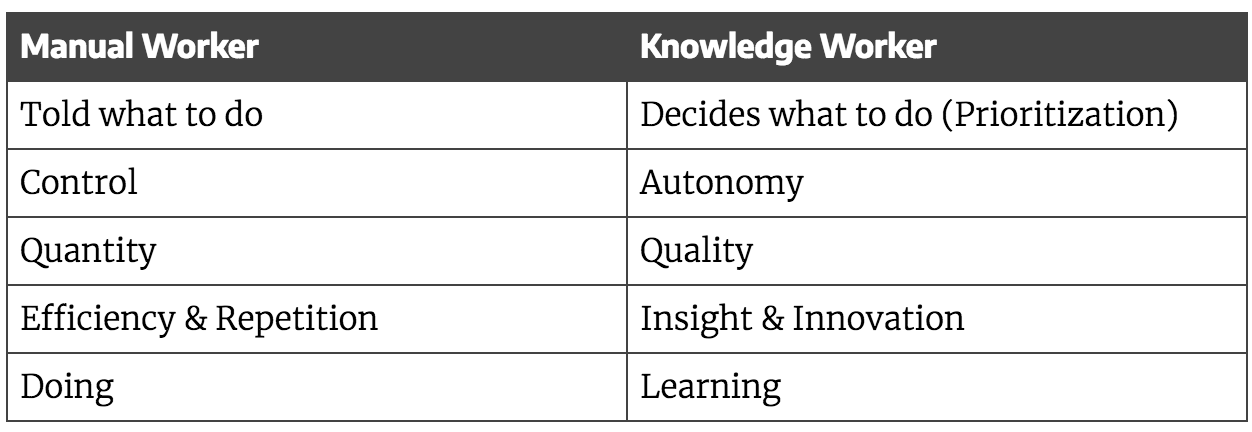

In one of his great manifestos, Drucker makes the case for the importance of knowledge worker productivity:

“The most important, and indeed the truly unique, contribution of management in the 20th century was the fifty-fold increase in the productivity of the manual worker in manufacturing. The most important contribution management needs to make in the 21st century is similarly to increase the productivity of knowledge work and knowledge workers.”

This premise begs the question, “As knowledge workers, how do we increase our own productivity?”

If you read the latest “productivity porn,” the key to productivity is adopting the latest app, hack, or habit.

Drucker answers the productivity question at a deeper level, and his answer helps us think about what truly makes us productive in the long run.

Here are Drucker’s six factors to knowledge worker productivity:

- Prioritization. Knowledge worker productivity demands that we ask the question: “What is the task?”

- Autonomy. It demands that we impose the responsibility for their productivity on the individual knowledge workers themselves. Knowledge workers have to manage themselves.

- Innovation. Continuing innovation has to be part of the work, the task and the responsibility of knowledge workers.

- Learning. Knowledge work requires continuous learning on the part of the knowledge worker, but equally continuous teaching on the part of the knowledge worker.

- Quality. Productivity of the knowledge worker is not — at least not primarily — a matter of the quantity of output. Quality is at least as important.

- Purpose. Finally, knowledge worker productivity requires that the knowledge worker is both seen and treated as an “asset” rather than a “cost.” It requires that knowledge workers want to work for the organization in preference to all other opportunities.

What

makes Drucker’s knowledge worker productivity factors particularly

interesting is twofold. First, almost all of the factors are the exact

opposite of what makes a manual worker productive. Second, many

knowledge workers today still

organize their careers more like manual workers and almost exclusively

focus on efficiency, working hard, and high daily output.

As you advance in your career to higher levels of knowledge work, this process becomes the ultimate way to create value.

Drucker breaks down the difference between quality and quantity in the manifesto:

In most knowledge work, quality is not a minimum and a restraint. Quality is the essence of the output. In judging the performance of a teacher, we do not ask how many students there can be in his or her class. We ask how many students learn anything — and that’s a quality question. In appraising the performance of a medical laboratory, the question of how many tests it can run through its machines is quite secondary to the question of how many test results are valid and reliable.

Productivity of knowledge work therefore has to aim first at obtaining quality — and not minimum quality but optimum if not maximum quality. Only then can one ask: “What is the volume, the quantity of work?

The application of 20th century Statistical Theory to manual work is the ability to cut (though not entirely to eliminate) production that falls below this minimum standard.

This simple difference of optimizing for quality over quantity in one’s work changes the game.

Quantity: Work harder with processes in place to make fewer errors.

Quality: Define what quality is and then create a process that maximizes it.

We see this distinction at play in Warren Buffett’s career. Buffett’s genius is that he prioritizes learning so he can have higher quality insights.

Throughout Buffett’s career, he has only made a handful of investments per year. Describing his approach, Buffett says:

“The trick in investing is just to sit there and watch pitch after pitch go by and wait for the one right in your sweet spot. And if people are yelling, ‘Swing, you bum!,’ ignore them.”

Amazingly,

there have been multi-year periods where Buffett has made zero

investments. Can you imagine how difficult it would be to wake up every

day for years and not invest if you were a professional investor?

Buffett

understands and actually follows through on the logical implications of

what it means to be a knowledge worker in a knowledge society.

Buffett

and the Learner’s Lifestyle converts time into value in a completely

different way than the typical approach to work, which borrows from the

culture of routine, manual work.

Here’s the knowledge work assembly line for the 21st century:

Buffett is not alone in remaking his schedule around insight.

In my previous articles,

I share the stories of many more entrepreneurs and leaders who have

made time for deliberate learning throughout their entire careers. Other

lumineer readers include billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban

(three-plus hours a day), billionaire entrepreneur Arthur Blank

(two-plus hours a day), billionaire investor David Rubenstein (six books

a week), billionaire entrepreneur Dan Gilbert (one to two hours a day),

Oprah Winfrey (credits reading for much of her success), Elon Musk (two

books a day when he was younger), Mark Zuckerberg (a book every two

weeks), Jeff Bezos (hundreds of science fiction novels by the time he

was 13), and CEO of Disney, Bob Iger (gets up every morning at 4:30 a.m.

to read).

The

power of the Learner’s Lifestyle has existed for a long time. But, we

are at a unique point in history that is increasing the returns on this

lifestyle.

There’s a famous parable of a consultant that illustrates this perfectly.

The Rise Of The Learner’s Lifestyle

There once was a power plant that shut down because of a mechanical failure. As you can imagine, this was a disaster!

The employees went all hands on deck trying

The employees went all hands on deck trying to fix the problem for days, but no one could find its source.

In desperation, the plant manager reached out to a consultant.

Not

long after, the consultant confidently walked into the plant and spent a

few hours very deliberately walking around to understand each of the

components and how they interacted with each other. He spent several

more hours asking the plant manager and employees a series of questions.

Finally, he went back to a part of the plant he had previously inspected and pressed a button.

Amazingly, the entire plant came back to life. The lights turned on. The machines started whirring. The problem was fixed.

“Oh my god!” the manager exclaimed. “You did it. How much do I owe you?”

“$100,000,” the consultant confidently replied.

“What?! $100,000. All you did is push a button! How do you account for that?”

The consultant pulled out a pencil from behind his ear and grabbed an invoice template from his pocket.

Next, he wrote down the following:

Pushing a button: $1

Knowing which button to push: $99,999

This parable gets at the heart of the power of insight.

In certain situations, having insight can provide 1,000 times the leverage.

We

live in a unique time: Insight is the key to solving more and more

problems, and the dividends on insight are increasing because we live in

an increasingly global, digital, technological, and complex world.

Here’s why there has never been a better time to adopt a Learner’s Lifestyle:

- Globalization leads to larger markets for our insights. Imagine if that same $100,000 insight could then help 1,000 other power plants (customers) across the world. That would effectively increase the value of this one insight a thousandfold. A larger market means that it’s worth spending more time upfront to acquire the insight.

- Digitization means we can scale our insight at no cost. Digitization makes it possible for us to scale ourselves so we can service those 1,000 other power plants without having to travel to each one individually. We can do this through online education. As product categories become increasingly digital via 3D printing, the leverage that comes from insight will get even higher. Harvard professor Yochai Benkler captures the significance of this shift in his book The Wealth Of Networks:

“The removal of the physical constraints on effective information production has made human creativity and the economics of information itself the core structuring facts in the new networked information economy.”

- Technology is increasing our manual work productivity exponentially. Every job includes “doing.” But, we can now can do more in dramatically less time. In other words, the gap between having an idea and realizing it in the physical world is shrinking. Because of this, there is a growing number of “Million-Dollar, One-Person Businesses” (aka incredibly profitable businesses run by just one founder and NO employees), and the largest companies in the world today have fewer employees per dollar of revenue than the previous generation’s.

- Complex problems require deeper levels of cross-disciplinary learning. The most complex problems that individuals, businesses, and society faces are innately cross-disciplinary. People who spend more time learning across fields are at an advantage to have unique insights to solve these problems.

- There are more and more ways to turn insights into value. Some of the ways include: creating new knowledge using the scientific method (science), creating a new paradigm or approach in a field (thought leadership), sharing your existing knowledge (teaching, consulting, coaching), working for a company, starting a company, or using your knowledge to train an artificial intelligence algorithm.

- The world is changing faster and faster. As the environment changes more quickly, it takes more and more adaptation to stay in the same place. This is known is the Red Queen Effect and the Law Of Requisite Variety. Learning, thinking, experimentation, and insight are how we adapt.

Bottom line: We’re

in a time of a lot of technical change. That technical change is

resulting in cultural change — specifically, how we work and

live — which is increasing the return on insight. Hard work is critical

to success. But the scales are tipping toward insight.

This brings me to my next point: the Learner’s Lifestyle is the perfect fit to the ways we live and work now.

Dream Job Alert: Get Paid A 6-Figure Or 7-Figure Salary To Read, Think, And Experiment For Hours A Day From Wherever You Want

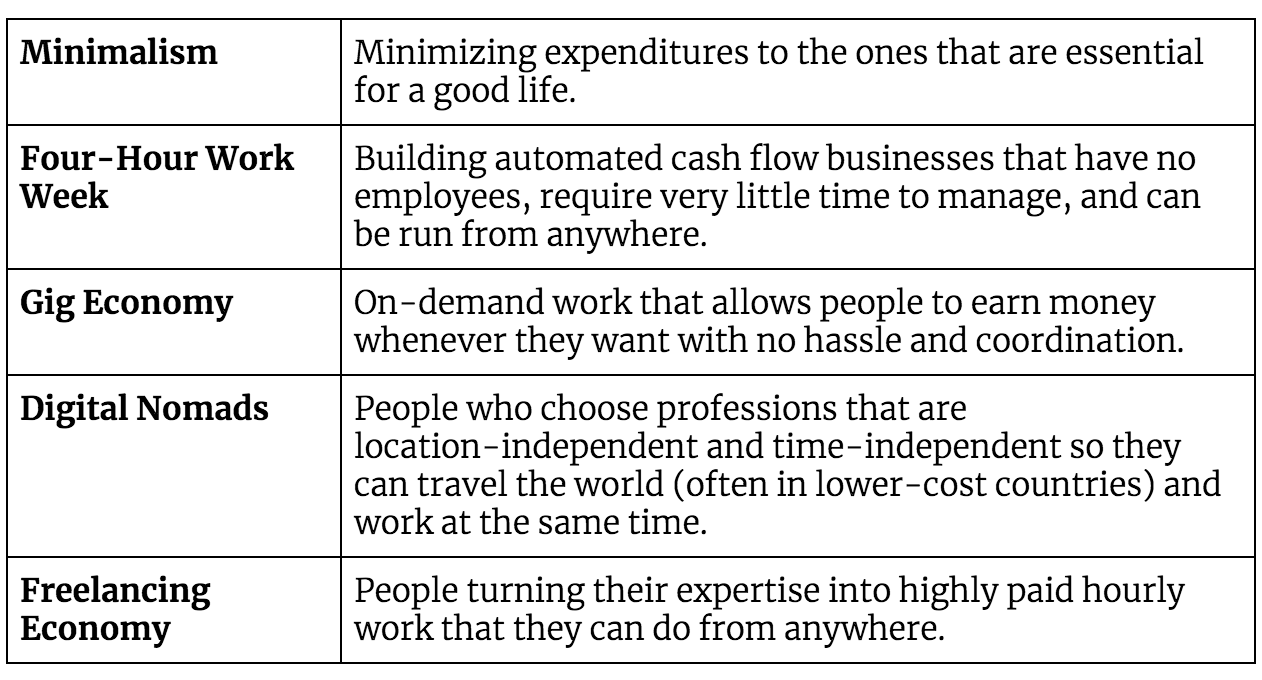

Over the last two decades, many professionals have moved away from more traditional work lifestyles:

- Working at one company their whole life

- Working 70-plus hours per week (while subordinating health, learning, family, and friends to career success)

- Keeping a professional front at work (while leaving yourself at the door)

…to the following Lifestyle Design Movements:

While all of these movements are different, they also have a lot in common. People don’t want to be forced to do:

- Work they don’t want to do

- When they don’t want to do it

- With people they don’t want to be around

- In stifling environments (that’s a repetitive stress injury waiting

to happen)

… just to make barely enough money to feed themselves and their family.

Buffett’s

contribution is a new category of lifestyle design — The Learner’s

Lifestyle. This category of work is particularly well-suited for people

who:

- Are lifelong learners

- Deeply love learning

- Enjoy virtual work

- Appreciate flexibility

- Are long-term thinkers

- Want to get paid for impact rather than time

My only regret is that I wasn’t exposed to this as a life and career path earlier, as I’m perfectly suited for it.

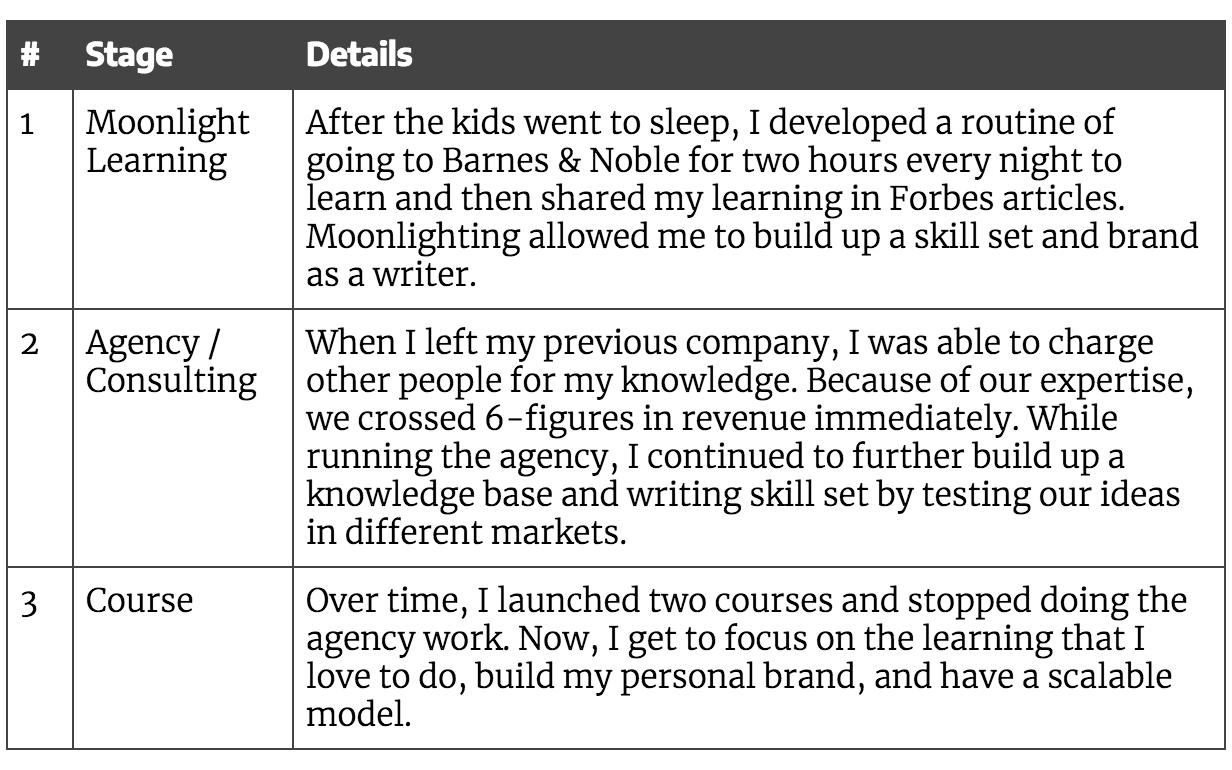

Here’s my journey toward it unfolded…

My Story: From Burned-Out Entrepreneur To The Learning Lifestyle

When

I first heard about Warren Buffett’s Learner’s Lifestyle, my kids were 3

years old and 1 year old. My business required a lot of travel and

meetings. I was working so much it was hurting my health, my

relationship with my wife, and my relationship with my kids. In retrospect, I was burned out.

The

only learning time I had was once the kids were asleep. However, by

that point, my energy was so shot that my routine became:

- Flop on the couch.

- Flip through bad TV options.

- Be disappointed that there was nothing I wanted to watch.

- Watch something completely mind-numbing.

At

the time, my daughter and I were occasionally watching “Hannah

Montana.” I’m embarrassed to say that I watched an episode alone far

more than once.

That was my rock bottom — watching a preteen sitcom by myself and enjoying it.

Today — six

years later — I spend 4–5 hours a day reading and thinking, and I view

it as fundamental to what I do. I have one meeting per day or so. I take

a 1–2 hour break in the middle of the day. When the kids go to bed, I

go for a walk with our dog while listening to audiobooks.

So, how did I go from watching “Hannah Montana” to leading a Learner’s Lifestyle where learning is baked into my day?

Of

course, there were many more detailed steps (which I will go into my

next article), but here are the two key ideas you need to know now so

you can begin the journey or go to the next level.

Two Steps To Kickstart Your Learner’s Lifestyle

There are two steps you can take right now:

Step #1: Put yourself in jobs, professions, companies, and industries where you are valued for your insight.

As

life goes by, we are presented with choices about the people we

collaborate with, the bosses and mentors we learn from, the projects we

take on, and the professions and industries we join.

Each of these choices has a profound impact on our ultimate learning.

At

the extreme end of the spectrum, someone stocking shelves at Wal*Mart

is only going to be valued for their physical effort. Similarly, a

white-collar worker who does the same thing over and over is primarily

going to be valued for their effort and accuracy.

In

the middle of the spectrum, a rapidly-evolving industry is more likely

to appreciate new insights and innovations than one that is changing

slowly.

At

the other end of the spectrum, a long-term value investor like Warren

Buffett can get an incredible return on investment by only making a

handful of big investment decisions per year. Entrepreneurs must rapidly

learn several disciplines in order to succeed and they live and die by

their own decisions.

The pathway that I followed included the following steps:

Each stage of the journey was essential to the next.

Step #2: Increase the leverage of your insights.

As you improve your learning and thinking ability, the value of your insights multiplies.

To take advantage of this multiplier, you need to put time into learning and learn how to learn more effectively.

This

way, your knowledge will compound upon itself, and over time, your

insights will become your durable competitive advantage in your career.

Start Compounding Your Knowledge Right Now

If

you’re serious about building your own Learner’s Lifestyle, and want to

make learning your competitive advantage, attend my free Learning How

to Learn Webinar. In just 2 hours, you will learn:

- How to find one hour per day for reading and learning even if you are really busy and overwhelmed

- How to 10x the results you receive from each hour of learning, and double them right away with a simple, little-known technique

- How to systematically apply what you learn to increase your profit and income

— — —

Michael Simmons

Learning

How To Learn Speaker & Teacher / Serial Entrepreneur / Bestselling

Author / Forbes, Fortune, Time, HBR Contributor / Site: http://t.co/T32xDLUBLJ

The Mission

We publish stories, videos, and podcasts to make smart people smarter. Subscribe to our newsletter to get them! www.TheMission.co

Responses

Applause from Michael Simmons (author)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)